Northwestern Medicine investigators have discovered that a microtubule regulatory protein inhibits early HIV type 1 (HIV-1) infection, according to findings published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Mojgan Naghavi, Ph.D., professor of Microbiology-Immunology and a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, was senior author of the study.

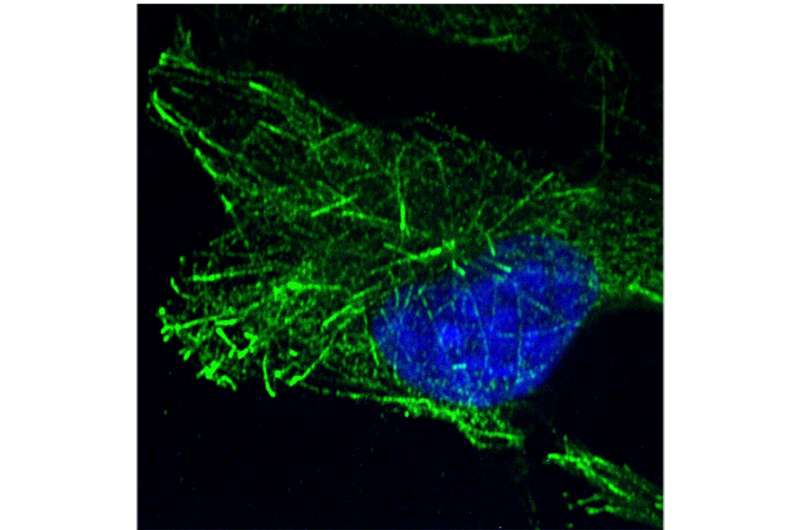

Many viruses require the dynein-dynactin motor-adaptor complex, which is responsible for the intracellular transport of cargos along microtubules on a cell’s cytoskeleton to reach the nucleus. Viruses exploit this complex to reach the nucleus and initiate infection.

Many viruses bind directly to microtubule motor proteins to travel within the cell, but previous work has shown that HIV-1 uses different cellular mechanisms to engage motor adaptors indirectly. In addition, unlike many viruses, HIV-1 does not require the protein dynactin-1 (DCTN1)—the core component of dynactin cargo adaptor for dynein—and the significance of this phenomenon has remained unknown, according to the authors.

By analyzing cells infected with HIV-1, Naghavi and colleagues found that DCTN1 inhibits early HIV-1 infection by interfering with the ability of the viral core, or the capsid shell surrounding the genome of the virus, to interact with critical cofactors (non-protein chemicals) within the host cell.

Specifically, DCTN1 competes for binding to HIV-1 particles with the cytoplasmic linker protein 170 (CLIP170), a microtubule plus-end tracking protein (+TIP), that the investigators had previously shown regulates the stability of viral cores after entry into the cell.

In the current study, they discovered that DCTN1 influences infection not as a component of the dynactin complex but instead as a +TIP that binds to and isolates CLIP170 from interacting with incoming HIV-1 particles.

“This negative function of DCTN1 in regulating +TIP functions outside the dynactin complex offers a rationale for why HIV-1 might have evolved away from DCTN1 as a means to engage dynein,” Naghavi said. “Our findings not only provide an explanation as to why HIV-1 has evolved away from using DCTN1 as a motor adaptor, but it also reveals mechanistic insights into the broader functional contributions of +TIPs in controlling HIV-1 infection.”

According to Naghavi, the findings could improve the development of novel therapeutic strategies to treat HIV-1, as current drugs targeting microtubules in cells, such as those currently used in chemotherapy, are toxic.

Source: Read Full Article