Older adults who hold reading material at arm’s length to bring it into focus are actually taking on the work that their eyes once did. It’s a literal lack of accommodation: the process by which the eye’s lens normally morphs from an ellipsoid to a more spherical shape when shifting focus between distant and nearby objects, or vice versa.

As people age, the lens no longer responds as dutifully to the muscle and connective bands that together reshape it. For most, that accommodation fails completely by age 55, leaving them unable to focus on nearby objects. When older adults undergo cataract surgery, their native lenses sometimes get replaced with accommodative intraocular lenses (AIOLs) that not only clear their cloudy sight but also attempt to restore accommodation. Unfortunately, the average AIOL restores just 20% of it.

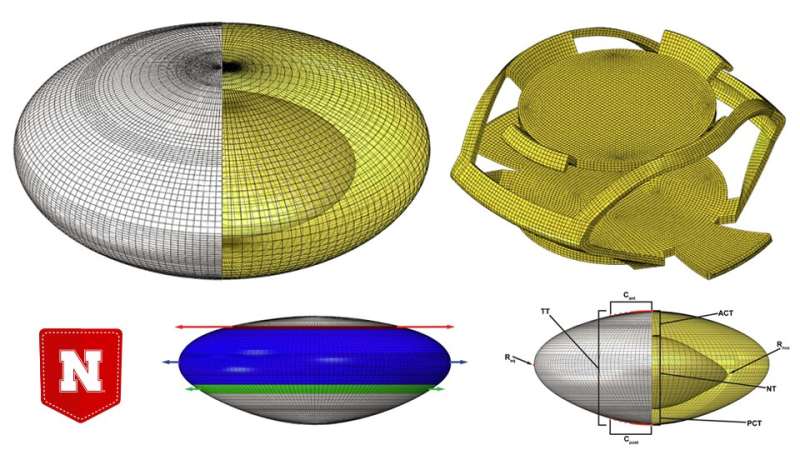

Improving that percentage depends on predicting mechanical interactions among an AIOL, the lens capsule housing the AIOL, and the muscle-band apparatus controlling accommodation. Nebraska’s Ryan Pedrigi and Kurt Ameku recently developed the first model designed to make those predictions, which could consequently help project how an implanted AIOL will perform.

Unlike prior efforts to model the native lens, the duo’s 3D model incorporates a nonlinear framework that better describes the lens capsule’s mechanics. It’s also the first to account for a pre-strain within the capsule that originates from native lens pressure identified by the researchers.

The duo calibrated its model using eight geometric variables taken from native lenses. That ultimately allowed the researchers to assess AIOL performance by accurately simulating interactions between an implanted AIOL and the post-surgery lens capsule of a 65-year-old.

Source: Read Full Article