Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The baby monitor crackled at 5:30 p.m. It was Oct. 26, 2020.

“Susan, I need you to come in here,” said 44-year-old Rogelio Lechuga, who was isolating with COVID-19 in the rear bedroom of the house he rented with his wife and three children in Mesa, AZ.

“Ro,” as everyone called him, had moved to the U.S. from Mexico at age 14 and had worked a variety of jobs before earning a college degree and becoming a salesman for a water filtration company. He and Susan met online in 1998. When they finally met in person at the airport, Ro greeted her with a dozen roses and a balloon bouquet that flew away when he hugged her. They had been married for 21 years.

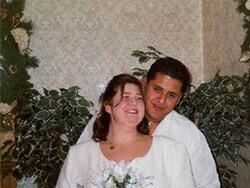

Ro and Susan Lechuga on their wedding day.

Susan had been looking after Ro for more than a week. She masked up, donned gloves, and tied up her hair in a ponytail. When she entered the room, she immediately noticed he looked more tired than usual and was having trouble breathing. She measured his oxygen level and blood pressure, but she says neither was at emergency levels. Still, his discomfort worried her, and given his underlying diabetes and kidney disease, she told him she was calling an ambulance. He did not argue, although he wanted to drive himself to avoid the expense.

Susan helped him shower, got him fresh shorts and a T-shirt, told the kids to go to their rooms, then stepped outside to call 911.

“By this point, I was frantic,” she recalls.

“I didn’t know how to talk to the ambulance people. I kept calling Ro the ‘patient.’ They [the dispatcher] asked me to check his pulse, so I ran back to his room. He was sitting in his recliner, slumped over and drooling. They told me to start CPR, but he’s 5′ 10″ and I’m 5′ 2″, and I couldn’t get him out of the chair. All I could think to do was grab his face and scream at him not to die.”

COVID-19 was rampaging through Arizona at the time. The morgues were full and bodies were being stored in refrigeration units. When the paramedics arrived, they were wearing full protective gear. To a child’s sensibility, they probably resembled aliens.

“The paramedics were in there for about 10 minutes,” continues Susan, hesitating now and then to choke back emotion. “The kids were still in their rooms, but they heard the machines and the screams of ‘Clear!'”

“I was sitting in the rocking chair in the front room, texting friends and family about what was happening, expecting someone to come out at any moment and say, ‘Everything is under control, we’re taking him to so-and-so hospital.'”

Instead, the fire chief came out holding Ro’s wedding ring. “He handed it to me and said, ‘We lost him.”’

She remembers that a social worker who had come with a crisis team looked at her and suggested she tell her children.

Ro Lechuga was 44 when he died of COVID-19.

“As crazy as it sounds, I didn’t want to tell the kids. I wanted to protect them,” Susan says. But she sat the kids together on the bunk bed and broke the news.

“I told them, ‘Mommy did everything she could, but we lost Dad.’ Rodrigo, my baby [age 6], got very sad and clingy. He just wanted his mommy. My middle son, Rowen [age 13], tried taking the blame, saying maybe if he had been a better son and done CPR, he could have saved him. My daughter, Roana [age 19], secluded herself away.”

Susan says Ro’s body remained in the bedroom for 5½ hours while the police and coroner completed their work. At 11:45 p.m., a funeral director finally wheeled out Ro on a gurney covered by a red velvet blanket.

“That was the last time the kids saw their father,” Susan says. “There was never a funeral. We said our final goodbyes in our front room.”

A Unique Loss

Rodrigo, Rowen, and Roana are just three of the more than 214,000 children and teens in the U.S. (and more than 6 million worldwide) who have lost a parent or grandparent caregiver to COVID-19. Minority children like the Lechugas have been disproportionately affected. (American Indian kids are four times more likely to have lost a parent or primary caregiver to COVID-19, Blacks and Hispanics 2.5 times, and Asians 1.6 times.) In all, 1 in every 340 children in the U.S. lost a parent or other caregiver to COVID-19.

These statistics prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), and the Children’s Hospital Association to jointly declare a “national state of emergency in children’s mental health.”

The Hidden Pain report, released in December 2021 by the nonprofit advocacy group COVID Collaborative, helped raise awareness about this issue by uncovering those previous statistics and updating them online. But it also went beyond the data to describe the broader challenges ahead.

Indeed, losing a parent is one of the most significant experiences a child can have. But losing a parent or primary caregiver to COVID-19 can be even worse.

Two prominent psychiatrists shared their thoughts on this for this story. Asim Shah, MD, is a professor and executive vice chair of the Menninger Department of Psychiatry at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Warren Y.K. Ng, MD, is the president of the AACAP and a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York. Both are on the front lines of helping children who lost a parent to COVID-19. They defined six distinct challenges that must be kept in mind when counseling them.

Trauma: Shah has counseled survivors of 9/11 and Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey. He’s noted that while those disasters were over in a few hours, COVID-19 has been relentless for a long time, which adds to the trauma.

The images of people on ventilators, bodies being stored in refrigerated trailers, the daily death counts, and the general confusion about how the virus is transmitted and how to protect yourself — especially during the pandemic’s early stages — all resulted in unprecedented levels of stress, fear, and trauma for adults, let alone children. These kids have been through the equivalent of war.

Stigma: Ng works with racially ethnic minority communities in northern Manhattan. It’s a high-density population, with many families packed into high-rise apartment buildings. It’s the type of living arrangement where everyone knows everyone’s business.

At the height of the pandemic, Ng says, people were ostracized for having COVID. It’s like they had a big red C on their door, warning neighbors to stay away.

As the pandemic progressed, the stigma grew beyond the disease itself. Anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers were considered stupid or selfish by some. If they contracted the virus, they were seen as deserving the consequences.

“I have a very close friend with two kids, ages 7 and 11, who is a nurse in Arkansas,” Shah says. “She wore a mask all the time, but her husband didn’t believe in masking. He believed this was all made up. Unfortunately, he got COVID and was on a ventilator for 29 days. Before dying, he admitted that he should have listened to his wife and wore a mask. He died with guilt, and he passed on that guilt to his kids.”

Blame: If a child brought home the virus that eventually killed a parent or caregiver, or if he or she, like 13-year-old Rowen Lechuga, feels they could have done something to save them, that can eat away at one’s mental health. The memory is a cruel and persistent reminder that you may be responsible. And that can have devastating effects.

Ng tells the story of a 9-year-old boy he treated whose father died of COVID. Both parents were in the health care field, so they didn’t have the luxury of working remotely. And because of limited resources, they worked opposite shifts.

The father was sick at home while the mother was working nights. The boy was sleeping in bed with his dad when he passed away, and he didn’t realize it until his mom got home the following morning. He was distressed that his father wouldn’t wake up and that his mother was so overwhelmed and grief-stricken. Having to quarantine afterward compounded their situation.

“The boy became very preoccupied with wanting to join his father,” Ng recalls. “He wanted to die and be asleep forever. He was at that stage in his development where he didn’t quite understand what death meant or what had happened to his father, and why nobody could come visit. All this furthered his sense of aloneness, sadness, and trauma. He also had a sense of guilt that maybe he had done something wrong. All this alarmed the mother, and she brought him in for treatment. Fortunately, we were able to work through the confusion and help him understand that it wasn’t his fault.”

Lack of closure: At the height of the pandemic, in-person funerals and memorial services were canceled. Such rituals for honoring a life are important to the healing process. But instead of feeling the love and support of family and friends, survivors often felt abandoned.

Even goodbyes were hard to come by. If a loved one was hospitalized, they were often isolated in ICUs that didn’t permit visitors or, because of being on ventilators, they were uncommunicative. If there was a chance for some final interaction, it was usually the partner who got priority. In many cases, the situation was considered too much for children to be exposed to.

“The trauma people had at that time is just unimaginable,” Shah says. “Consider you’ve just lost a loved one: 1) You cannot see them, b) You cannot go to their funeral, and c) You cannot even come close to their dead body. It was treated like a contaminated fixture. All those things combine to multiply the trauma.”

Financial insecurity: Dan Treglia, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and a co-author of Hidden Pain, says the death of a parent or primary caregiver often has “cascading consequences” because it disproportionately affects families with less financial resources.

“The child loses not just a caregiver but a breadwinner,” Treglia explains. “Suddenly, the family can no longer afford to live in the same place. Suddenly, they’re moving or become homeless or food insecure. Suddenly, they no longer have health insurance. This creates all kinds of other challenges.”

Ng cites a United Hospital Fund report for New York State that found that 50% of children who lost a parent or caregiver were likely to enter poverty, with 23% at risk to enter foster or kinship care. “These compounding factors add to the level of distress these kids may experience,” he says.

Ongoing reminders: Although the pandemic has subsided somewhat and we know much more about the virus, COVID is still far from being out of the news, and that can be a cruel reminder for families who’ve lost loved ones.

“A child’s home is their sanctuary,” Ng says, “but for many it suddenly became unsafe. Their world was turned inside out. They thought that home and family meant safety and security, but now with COVID-19 there’s this danger within.”

“Even though my husband died a year and a half ago, every single day my children are hearing about what killed their dad,” says Susan Lechuga, who moved to California shortly after Ro’s death to be closer to family. “If he had died in a car accident, I wouldn’t have to worry about turning on the TV and hearing there were 2,598 car accident deaths today. But if I turn on CNN, I can guarantee you that in 10 minutes there’s going to be something about COVID.”

“We have yet to be able to say this is over, the pain can now heal,” she continues. “The media, politicians, and society keep throwing it in our faces every day, and we cannot step out of this cycle of grief.”

Shah, who practices psychiatry in the largest outpatient network in Houston, is also frustrated.

“People are doing things individually, but we’re not doing a whole lot as a country,” Shah says. “I don’t see any efforts on a state or federal level. This is not the county’s problem, it’s the country’s problem. We need a nationwide plan that says, ‘These are the hotlines; here’s where you can go to get some help.’ But none of that is happening.”

Treglia agrees. “It’s an extraordinary problem,” he says. “This is an unprecedented level of parental and caregiver loss, and it’s the most vulnerable children who are being affected. We need a robust response.”

Hidden Pain states that 5% to 10% of children who lost a parent to COVID-19 will experience “traumatic, prolonged grief that requires clinical intervention.”

So what exactly will that take?

Find Every Child

To aid all the affected kids and families, the report makes 20 recommendations. These include expanding access to mental health care in schools and creating a COVID-19 Bereaved Children’s Fund that will provide short-term financial assistance and further support their mental health needs.

The report has succeeded in raising public and political awareness about this issue (President Joe Biden mentioned these kids specifically in an April White House memo).

But the biggest challenge may be logistical: identifying all of the children.

The Lechugas.

“That’s the hardest piece to all of this,” says Catherine Jaynes, PhD, senior director of external affairs for the COVID Collaborative. “There’s no systemic way for us to know who has been left behind. During the height of the pandemic, synagogues, churches, and schools were closed and that took away a mechanism for knowing how many children have been impacted.”

Jaynes says her organization is working with various government departments and the Biden administration to “create a coordinated response.” This summer, the Collaborative will also work to “bring awareness of this issue to schools,” Jaynes says, and convince them to add a box to student registration forms that a parent or guardian can check if their child has lost a primary caregiver to COVID. Once identified, the child and family can then be connected to resources either at the school or in the area.

For Lechuga, it was a one-woman effort to get her kids the support they needed after their dad’s death.

A Mother Steps In

Lechuga went to her youngest son’s new school on the first day of enrollment and “told them straight-up, ‘I’m a new resident, I lost my husband to COVID, and I’m not sure how my son is going to do here.'”

They met with the school psychologist, who referred them to a local mental health agency. Rodrigo has since completed the therapy and is doing better. His older brother is still in the program and improving. (Susan says her daughter has resisted therapy.)

“But I needed to be proactive,” Lechuga says. “You have to speak up and let your needs be known.”

Resources to Help

Although no government program (yet) specifically benefits children who lost a parent to COVID-19, resources are available. Here are three places to start:

COVID Collaborative Clearinghouse: This is a comprehensive resource library for families that lost a parent to COVID-19. It features nearly 100 articles divided into four sections (Understanding Grief, Financial Support, Supportive Experiences, and Educator Resources). The resources include activity sheets for grieving children and teens, information about COVID-19 funeral assistance, a bereavement camp directory for youths, and various grief guides for teachers and mentors.

Grief-Sensitive Schools Initiative: Sponsored by New York Life, this free program strives “to better equip educators and other school personnel to support grieving students.” A trained ambassador gives a preliminary 20-minute presentation on the topic to teachers and administrators. Qualifying schools can receive $500 grants to start them thinking about ways to become more grief sensitive.

Nearly 4,000 schools (K-12) are participating nationwide. The New York Life Foundation is also targeting Children’s Grief Awareness Month in November, potentially including a National Day of Remembrance for parents and caregivers lost to COVID-19.

National Alliance for Children‘s Grief: Ng notes that kids progress through four stages of cognitive development. What level they’re at affects how they understand death and grieve. The resources on this site are tailored to these stages. “You can’t assume all kids are the same,” Ng says. “It’s important for us to ask if they have questions and encourage them to communicate, because what they think is happening might be very different from what actually occurred.”

The Safety Net of Support

The loss of a parent or primary caregiver can leave a child feeling very alone, which makes it important that they get love and support from a larger safety net.

The Lechuga family’s memorial to Ro.

“It starts with family,” says Ng, the president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “Then there’s their faith-based community, their pediatrician or primary care doctor, their school and its health services, and finally the community mental health services and treatments that are available if needed.”

Last Feb. 8, on what would have been Ro’s 45th birthday, Lechuga and her children planted a white peach tree in their backyard with a memorial stone.

“I picked the white peach tree because peaches were his favorite,” Lechuga says. “When we first met, he kept rubbing my arms. He told me my skin was the color of white peaches but they weren’t as sweet as me. That became his pet name for me: his white peach.”

“Whenever we go somewhere special that he would have enjoyed, we sprinkle some of his ashes there,” says Lechuga, who is studying to be a therapist. That way, when we return, we can have a little picnic and know he’s there with us.”

Source: Read Full Article