When scientists announced the complete sequence of the human genome in 2003, they were fudging a bit.

In fact, nearly 20 years later, about 8% of the genome has never been fully sequenced, largely because it consists of highly repetitive chunks of DNA that are hard to align with the rest.

But a three-year-old consortium has finally filled in that remaining DNA, providing the first complete, gapless genome sequence for scientists and physicians to refer to.

The newly completed genome, dubbed T2T-CHM13, represents a major upgrade from the current reference genome, called GRCh38, which is used by doctors when searching for mutations linked to disease, as well as by scientists looking at the evolution of human genetic variation.

Among other things, the new DNA sequences reveal never-before-seen detail about the region around the centromere, which is where chromosomes are grabbed and pulled apart when cells divide, ensuring that each “daughter” cell inherits the correct number of chromosomes. Variability within this region may also provide new evidence of how our human ancestors evolved in Africa.

“Uncovering the complete sequence of these formerly missing regions of the genome told us so much about how they’re organized, which was totally unknown for many chromosomes,” said Nicolas Altemose, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, and a co-author of four new papers about the completed genome. “Before, we just had the blurriest picture of what was there, and now it’s crystal clear down to single base pair resolution.”

Altemose is first author of one paper that describes the base pair sequences around the centromere. A paper explaining how the sequencing was done will appear in the April 1 print edition of the journal Science, while Altemose’s centromere paper and four others describing what the new sequences tell us are summarized in the journal with the full papers posted online. Four companion papers, including one for which Altemose is co-first author, also will appear online April 1 in the journal Nature Methods.

The sequencing and analysis were performed by a team of more than 100 people, the so-called Telemere-to-Telomere Consortium, or T2T, named for the telomeres that cap the ends of all chromosomes. The consortium’s gapless version of all 22 autosomes and the X sex chromosome is composed of 3.055 billion base pairs, the units from which chromosomes and our genes are built, and 19,969 protein-coding genes. Of the protein-coding genes, the T2T team found about 2,000 new ones, most of them disabled, but 115 of which may still be expressed. They also found about 2 million additional variants in the human genome, 622 of which occur in medically relevant genes.

“In the future, when someone has their genome sequenced, we will be able to identify all of the variants in their DNA and use that information to better guide their health care,” said Adam Phillippy, one of the leaders of T2T and a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) of the National Institutes of Health. “Truly finishing the human genome sequence was like putting on a new pair of glasses. Now that we can clearly see everything, we are one step closer to understanding what it all means.”

The evolving centromere

The new DNA sequences in and around the centromere total about 6.2% of the entire genome, or nearly 190 million base pairs, or nucleotides. Of the remaining newly added sequences, most are found around the telomeres at the end of each chromosome and in the regions surrounding ribosomal genes. The entire genome is made of just four types of nucleotides, which, in groups of three, code for the amino acids used to build proteins. Altemose’s main research involves finding and exploring areas of the chromosomes where proteins interact with DNA.

“Without proteins, DNA is nothing,” said Altemose, who earned a Ph.D. in bioengineering jointly from UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco in 2021 after having received a D.Phil. in statistics from Oxford University. “DNA is a set of instructions with no one to read it if it doesn’t have proteins around to organize it, regulate it, repair it when it’s damaged and replicate it. Protein-DNA interactions are really where all the action is happening for genome regulation, and being able to map where certain proteins bind to the genome is really important for understanding their function.”

After the T2T consortium sequenced the missing DNA, Altemose and his team used new techniques to find the place within the centromere where a big protein complex called the kinetochore solidly grips the chromosome so that other machines inside the nucleus can pull chromosome pairs apart.

“When this goes wrong, you end up with missegregated chromosomes, and that leads to all kinds of problems,” he said. “If that happens in meiosis, that means you can have chromosomal anomalies leading to spontaneous miscarriage or congenital diseases. If it happens in somatic cells, you can end up with cancer—basically, cells that have massive misregulation.”

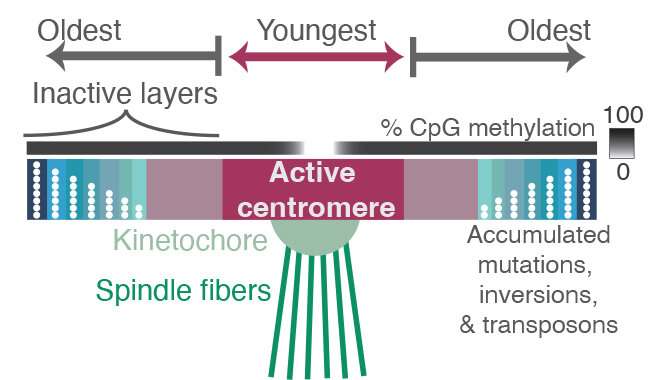

What they found in and around the centromeres were layers of new sequences overlaying layers of older sequences, as if through evolution new centromere regions have been laid down repeatedly to bind to the kinetochore. The older regions are characterized by more random mutations and deletions, indicating they’re no longer used by the cell. The newer sequences where the kinetochore binds are much less variable, and also less methylated. The addition of a methyl group is an epigenetic tag that tends to silence genes.

All of the layers in and around the centromere are composed of repetitive lengths of DNA, based on a unit about 171 base pairs long, which is roughly the length of DNA that wraps around a group of proteins to form a nucleosome, keeping the DNA packaged and compact. These 171 base pair units form even larger repeat structures that are duplicated many times in tandem, building up a large region of repetitive sequences around the centromere.

The T2T team focused on only one human genome, obtained from a non-cancerous tumor called a hydatidiform mole, which is essentially a human embryo that rejected the maternal DNA and duplicated its paternal DNA instead. Such embryos die and transform into tumors. But the fact that this mole had two identical copies of the paternal DNA—both with the father’s X chromosome, instead of different DNA from both mother and father—made it easier to sequence.

The researchers also released this week the complete sequence of a Y chromosome from a different source, which took nearly as long to assemble as the rest of the genome combined, Altemose said. The analysis of this new Y chromosome sequence will appear in a future publication.

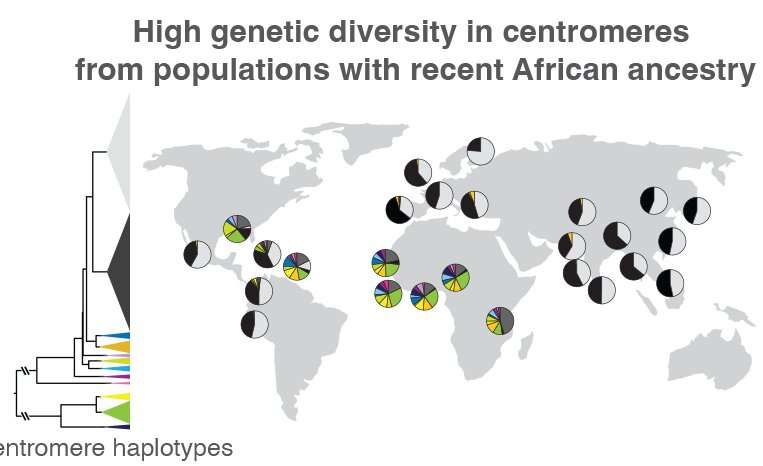

Altemose and his team, which included UC Berkeley project scientist Sasha Langley, also used the new reference genome as a scaffold to compare the centromeric DNA of 1,600 individuals from around the world, revealing major differences in both the sequence and copy number of repetitive DNA around the centromere. Previous studies have shown that when groups of ancient humans migrated out of Africa to the rest of the world, they took only a small sample of genetic variants with them. Altemose and his team confirmed that this pattern extends into centromeres.

“What we found is that in individuals with recent ancestry outside the African continent, their centromeres, at least on chromosome X, tend to fall into two big clusters, while most of the interesting variation is in individuals who have recent African ancestry,” Altemose said. “This isn’t entirely a surprise, given what we know about the rest of the genome. But what it suggests is that if we want to look at the interesting variation in these centromeric regions, we really need to have a focused effort to sequence more African genomes and do complete telomere-to-telomere sequence assembly.”

DNA sequences around the centromere could also be used to trace human lineages back to our common ape ancestors, he noted.

“As you move away from the site of the active centromere, you get more and more degraded sequence, to the point where if you go out to the furthest shores of this sea of repetitive sequences, you start to see the ancient centromere that, perhaps, our distant primate ancestors used to bind to the kinetochore,” Altemose said. “It’s almost like layers of fossils.”

Long-read sequencing a game changer

The T2T’s success is due to improved techniques for sequencing long stretches of DNA at once, which helps when determining the order of highly repetitive stretches of DNA. Among these are PacBio’s HiFi sequencing, which can read lengths of more than 20,000 base pairs with high accuracy. Technology developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies Ltd., on the other hand, can read up to several million base pairs in sequence, though with less fidelity. For comparison, so-called next-generation sequencing by Illumina Inc. is limited to hundreds of base pairs.

“These new long-read DNA sequencing technologies are just incredible; they’re such game changers, not only for this repetitive DNA world, but because they allow you to sequence single long molecules of DNA,” Altemose said. “You can begin to ask questions at a level of resolution that just wasn’t possible before, not even with short-read sequencing methods.”

Altemose plans to explore the centromeric regions further, using an improved technique he and colleagues at Stanford developed to pinpoint the sites on the chromosome that are bound by proteins, similar to how the kinetochore binds to the centromere. This technique, too, uses long-read sequencing technology. He and his group described the technique, called Directed Methylation with Long-read sequencing (DiMeLo-seq), in a paper that appeared this week in the journal Nature Methods.

Meanwhile, the T2T consortium is partnering with the Human PanGenome Reference Consortium to work toward a reference genome that represents all of humanity.

“Instead of just having one reference from one human individual or one hydatidiform mole, which isn’t even a real human individual, we should have a reference that represents everybody,” Altemose said. “There are various ideas about how to accomplish that. But what we need first is a grasp of what that variation looks like, and we need lots of high-quality individual genome sequences to accomplish that.”

Source: Read Full Article