Hair follicle miniaturization was a prominent feature of persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (pCIA) in breast cancer survivors who presented to four specialty hair clinics, and treatment with minoxidil (sometimes with antiandrogen therapy) was associated with improved hair density, according to a recently published retrospective case series.

“An improvement in hair density was observed in most of the patients treated with topical minoxidil or LDOM [low-dose oral minoxidil], with a more favorable outcome seen with LDOM with or without antiandrogens,” reported Bevin Bhoyrul, MBBS, of Sinclair Dermatology in Melbourne and coauthors from the United Kingdom and Germany.

The findings, published in JAMA Dermatology, suggest that pCIA “may be at least partly reversible,” they wrote.

The investigators analyzed the clinicopathologic characteristics of pCIA in 100 patients presenting to the hair clinics, as well as the results of trichoscopy performed in 90 of the patients and biopsies in 18. The researchers also assessed the effectiveness of treatment in 49 of these patients who met their criteria of completing at least 6 months of therapy with minoxidil.

Almost all patients in their series — 92% — were treated with taxanes and had more severe alopecia than those who weren’t exposed to taxanes (a median Sinclair scale grade of 4 vs. 2). Defined as absent or incomplete hair regrowth 6 months or more after completion of chemotherapy, pCIA has been increasingly reported in the literature, the authors note.

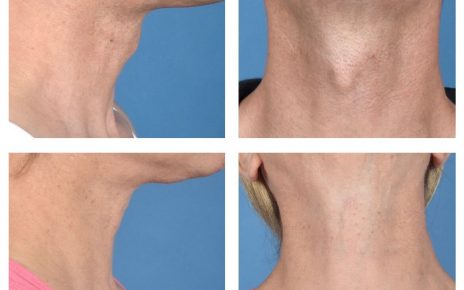

Of the 100 patients, all but one of whom were women, 39 had globally-reduced hair density that also involved the occipital area (diffuse alopecia), and 55 patients had thinning of the centroparietal scalp hair in a female pattern hair loss (FPHL) distribution. Patients presented between November 2011 and February 2020 and had a mean age of 54. The Sinclair scale, which grades from 1 to 5, was used to assess the severity of hair loss in these patients.

Five female patients had bitemporal recession or balding of the crown in a male pattern hair loss (MPHL) distribution, and the one male patient had extensive baldness resembling Hamilton-Norwood type VII.

The vast majority of patients who had trichoscopy performed – 88% – had trichoscopic features that were “indistinguishable from those of androgenetic alopecia,” most commonly hair shaft diameter variability, increased vellus hairs, and predominant single-hair follicular units, the authors reported.

Of the 18 patients who had biopsies, 14 had androgenetic alopecia-like features with decreased terminal hairs, increased vellus hairs, and fibrous streamers. The reduced terminal-to-vellus ratio characterizes hair follicle miniaturization, a hallmark of androgenetic alopecia, they said. (Two patients had cicatricial alopecia, and two had features of both.)

“The predominant phenotypes of pCIA show prominent vellus hairs both clinically and histologically, suggesting that terminal hair follicles undergo miniaturization,” Bhoyrul and coauthors wrote. Among the 49 patients who completed 6 months or more of treatment, the median Sinclair grade improved from 4 to 3 in 21 patients who received topical minoxidil for a median duration of 17 months; from 4 to 2.5 in 18 patients who received LDOM for a median duration of 29 months; and from 5 to 3 in 10 patients who received LDOM combined with an antiandrogen, such as spironolactone, for a median of 33 months.

Almost three-quarters of the patients in the series received adjuvant hormone therapy, which is independently associated with hair loss, the authors noted. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the pattern or severity of alopecia between patients who were treated with endocrine therapy and those who weren’t.

Asked to comment on the study and on the care of patients with pCIA, Maria K. Hordinsky, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and an expert in hair diseases, said the case series points to the value of biopsies in patients with pCIA.

“Some patients really do have a loss of hair follicles,” she said. “But if you do a biopsy and see this miniaturization of the hair follicles, then we have tools to stimulate the hair follicles to become more normal. …These patients can be successfully treated.”

For patients who do not want to do a biopsy, a therapeutic trial is acceptable. “But knowing helps set expectations for people,” she said. “If the follicles are really small, it will take months [of therapy].”

In addition to topical minoxidil, which she said “is always a good tool,” and LDOM, which is “becoming very popular,” Hordinsky has used low-level laser light successfully. She cautioned against the use of spironolactone and other hair-growth promoting therapies with potentially significant hormonal impacts unless there is discussion between the dermatologist, oncologist, and patient.

The authors of the case series called in their conclusion for wider use of hair-protective strategies such as scalp hypothermia. But Hordinsky said that, in the United States, there are divergent opinions among oncologists and among cancer centers on the use of scalp cooling and whether or not it might lessen response to chemotherapy.

More research is needed, she noted, on chemotherapy-induced hair loss in patients of different races and ethnicities. Of the 100 patients in the case series, 91 were European; others were Afro Caribbean, Middle Eastern, and South Asian.

Bhoyrul is supported by the Geoffrey Dowling Fellowship from the British Association of Dermatologists. One coauthor disclosed serving as a principal investigator and/or scientific board member for various pharmaceutical companies, outside of the submitted study. There were no other disclosures reported. Hordinsky, the immediate past president of the American Hair Research Society and a section editor for hair diseases in UpToDate, had no relevant disclosures.

This article originally appeared on MDedge.com, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Source: Read Full Article