Nearly 3 in 4 US physicians who responded to a recent Medscape poll say they see the practice of medicine as a calling rather than as a good profession or a job. This was equally true of male and female doctors, doctors 45 and older, and primary care physicians and specialists. The poll ran from July 26 to August 11.

Experts say a calling usually means feeling a deep sense of purpose about one’s profession, being personally invested in one’s work and an alignment of values. A job is primarily about earning a paycheck and a means to an end that can allow for personal investment in other areas of life.

Traditionally, doctors have said that medicine is a calling and doctors who don’t hold that view have experienced backlash or criticism. They may also be more likely to get burned out or retire earlier.

In addition, research shows that physicians who view the profession as a calling are more likely to go the extra mile for patients who need their help; work long hours, put their patients’ welfare before their own; and sacrifice home and family time for patient care.

That tendency to self-sacrifice has led some to question whether believing in a calling has inadvertently become harmful to physicians.

The Pros and Cons of a Calling

Dr Peter Yellowlees

“Viewing medicine as a calling is generally a positive thing for physicians and patients and it’s likely to make doctors more committed to their work and to ensuring that they deliver high quality evidence-based care,” says Peter Yellowlees, MD, MBBS, a distinguished professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Davis.

Respondents who feel called to medicine, for example, were most likely to say “I love practicing medicine and find it deeply satisfying,” and “I always wanted to be a doctor and feel that’s my mission in life.”

Primary care physicians who see medicine more as a calling report greater satisfaction in, for example, treating patients who struggle with substance dependence and obesity, the authors of a recent study in Mayo Clinic Proceedings wrote.

However, some physicians might go too far and sacrifice too much for the sake of their patients and neglect themselves and their families, says Yellowlees.

These doctors are so devoted to their patients that they work excessive hours and are constantly available to them. “Some may need their patients as much as their patients need them as a way of validating their own practice style,” he says. This can lead to burnout and a poorly integrated work and home life, says Yellowlees.

Doctors who feel called to practice medicine or feel that their work is meaningful and have some balance in their lives may also be protected from burnout, says Yellowlees. “If you don’t see much meaning in your career, there’s evidence that you’re more at risk of getting burned out, making more errors and having lower levels of patient satisfaction in practice.”

The Mayo Clinic Proceedings study looked at burnout and physicians’ sense of calling, and found that physicians who are more burned out are less likely to identify with medicine as a calling. Compared with physicians who reported no burnout symptoms, those who were completely burned out were less likely to find their work rewarding, see their work as one of the most important things in their lives, or think that their work makes the world a better place.

“Physicians who do not view medicine as a calling may assign relatively greater value to their work as a means to earn a living,” the authors write. “Therefore, one potential consequence of professional burnout is physicians who are less intrinsically and prosocially motivated because they see medicine less as a calling but more as a job — a way to simply earn a paycheck.”

Physicians Who Don’t Feel Called to Medicine

Of the US respondents to the Medscape survey, 1 in 5 said they do not feel called to medicine. They were most likely to say, “I enjoy my career, but find other areas of life equally fulfilling,” “I feel it’s a good career, but I could see myself in another career,” and “I enjoy the pay and prestige that comes with being a doctor but it’s not my whole life.”

This perspective can be quite positive for many physicians. “Those who see medicine as less of a calling may lead broader lives than allows for outside activities and relationships, which seems totally reasonable if they can strike a balance between their work and home lives,” says Yellowlees.

He cautioned against assuming that doctors who are less passionate about medicine or who enter medicine for economic reasons are less dedicated or less competent physicians than those who feel called. “They may seek different rewards and choose specialties with less human contact.”

Do Specialists and Primary Care Docs Feel Equally Called?

Although most specialists and primary care doctors feel called to practice medicine, there were some differences in their responses.

Specialists were slightly more likely to say they are willing to go the extra mile for patients who need their help, even after hours (51% v 42%); they love practicing medicine and find it deeply satisfying (54% v 42%); and if patients can’t pay them due to financial hardship, they will see them anyway (37% vs 26%).

Yellowlees said he’s not surprised by this. Specialists usually choose their area of practice, are generally better paid and receive more validation from patients of their worth, especially when they find a specific niche and become extremely good at it. “They always have the pressure of being an expert and to demonstrate their expertise,” he says.

Primary care doctors are more likely to experience pressure to work after hours and be constantly available to patients, he says. He recommends they learn to set limits on patients’ “increasingly unrealistic expectations of availability, especially in this age of easy access through patient portals.”

How Do Docs Outside the US Compare?

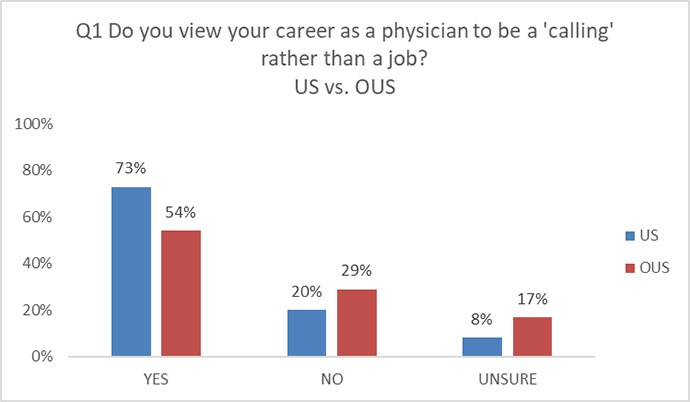

Physicians practicing outside the United States (OUS) were less likely to feel they were called to medicine. Slightly more than half (54%) of the 150 OUS respondents said they feel called to practice medicine, compared with 73% of US doctors.

The concept of a calling is not unique to the United States, but the big difference is that doctors in the US are paid a lot more than doctors in other countries, especially those who work for nationalized health systems, says Yellowlees, who has worked not only in the US but in the United Kingdom and Australia.

“Doctors in the US also receive a considerably higher level of respect from their communities,” he says.

Doctors outside the US were also more likely to say that they enjoy their medical career, but find other areas equally fulfilling.

Regardless of whether doctors feel called to medicine or not, it’s important for them to integrate their home life with their work life and look after themselves and their patients, Yellowlees says.

Christine Lehmann, MA, is a senior editor and writer for Medscape Business of Medicine based in the Washington, DC area. She has been published in WebMD News, Psychiatric News, and The Washington Post. Contact Christine at clehmann@medscape or via Twitter @writing_health.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article