Bruce “BJ” Miller Jr., a 19-year-old Princeton University sophomore, was horsing around with friends near a train track in 1990 when they spotted a parked commuter train. They decided to climb over the train, and Miller was first up the ladder.

Suddenly, electricity from the nearby powerlines arched to Miller’s metal watch, shooting 11,000 volts of electricity through his body.

An explosion ripped through the air, and Miller was thrown on top of the train, his body smoking. His petrified friends called for an ambulance.

Clinging to life, Miller was airlifted to the burn unit at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, New Jersey.

Physicians saved Miller’s life, but they had to amputate both of his legs below the knees and his left arm below the elbow.

“With electricity, you burn from the inside out,” said Miller, now 50. “The voltage enters your body — in my case, the wrist — and runs around internally until it finds a way out. That is often the lower extremities as the ground tends to ground the current, but not always. In my case, the current tried to come through my chest — which is also burned and required skin grafting — but not enough to spare my legs. I think I had a half dozen or so surgeries over the first month or two at the hospital.”

Waking Up to A New Body

Miller doesn’t remember much about the accident, but he recalls waking up a few days later in the ICU and feeling the need to use the bathroom. Disoriented, Miller pulled off his ventilator, climbed out of bed, and tried to walk forward, unaware of his injuries. His feet and legs had not yet been amputated. When the catheter line ran out of slack, he collapsed.

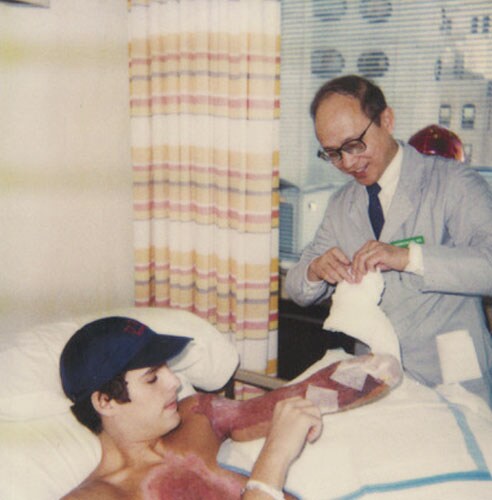

Friends visit BJ Miller in the hospital shortly after he was electrocuted.

“Eventually, a nurse came rushing in, responding to the ventilator alarm bells going off,” Miller said. “My dad wasn’t far behind. It became clear to me then that this was not a dream and [I realized] what had happened and why I was in the hospital.”

For months, Miller lived in the burn unit, undergoing countless skin grafts and surgeries. Because viable and nonviable tissue take time to be revealed after burns, surgeons take the minimum amount of tissue during each operation to give damaged tissue a chance to heal, he explained. In Miller’s case, his feet were amputated first and later, his legs.

“In those early days from the hospital bed, my mind turned to issues related to identity,” he said. “What do I do with myself? What is the meaning of my life now? I was challenged in those ways. I had to think through who I was, and who I wanted to become.”

Miller eventually moved to the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (now called The Shirley Ryan AbilityLab), where he started the grueling process of rebuilding his strength and learning to walk on prosthetic legs.

“Any one day was filled with a mix of optimism and good fight and 5 minutes later, exasperation, frustration, tons of pain, and insecurity about my body,” he said. “My family and friends held the gate for me in a way, but a lot of the work was up to me. I had to believe that I deserved this love, that I wanted to be alive, and that there was still something here for me.”

BJ Miller speaks with his psychiatrist, Dr Wu, in the early months after the accident.

Miller didn’t have to look far for inspiration. His mom had lived with polio for most of her life and acquired post-polio syndrome as she grew older, he said. When Miller was a child, his mom walked with crutches, and she became wheelchair-dependent by the time he was a teenager.

After the first surgery to amputate his feet, Miller and his mom shared a deep discussion about his joining the ranks of “the disabled,” and how their connection was now even stronger.

“In this way, the injuries unlocked even more experiences to share between us, and more love to feel, and therefore some early sense of gain to complement all the losses happening,” he said. “She had taught me so much about living with disability and had given me all the tools I needed to refashion my sense of self.”

From Burn Patient to Medical Student

After returning to Princeton University and finishing his undergraduate degree, Miller decided to go into medicine. He wanted to use his experience to help patients and find ways to improve weaknesses in the healthcare system, he said. But he made a deal with himself that he wouldn’t become a doctor for the sake of becoming one; he would enter the vocation only if he could do the work and enjoy the job.

“I wasn’t sure if I could do it,” he said. “There weren’t a lot of triple amputees to point to, to say whether this was even mechanically possible, to get through the training. The medical institutions I spoke with knew they had some obligation by law to protect me, but there’s also an obligation that I need to be able to fulfill the competencies. This was uncharted water.”

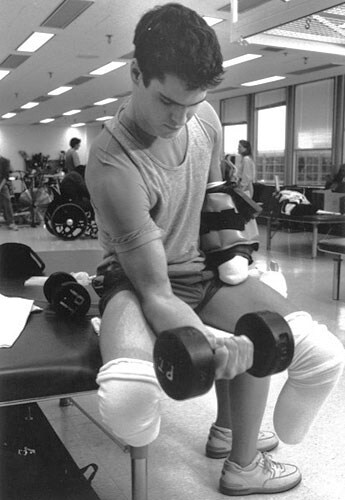

BJ lifts weights in the gym during physical therapy.

Because his greatest physical challenge was standing for long periods, instructors at the University of California, San Francisco made accommodations to alleviate the strain. His clinical rotations for example, were organized near his home to limit the need for travel. On surgical rotations, he was allowed to sit on a stool.

Medical training progressed smoothly until Miller completed a rotation in his chosen specialty, rehabilitation medicine. He didn’t enjoy it. The passion and meaning he hoped to find was missing. Disillusioned, and with his final year in medical school coming to an end, Miller dropped out of the Match program. Around the same time, his sister, Lisa, died by suicide.

“My whole family life was in shambles,” he said. “I felt like, ‘I can’t even help my sister, how am I going to help other people?’ ”

Miller earned his MD and moved to his parents’ home in Milwaukee after his sister’s death. He was close to giving up on medicine, but his deans convinced him to do a post-doc internship. It was as an intern at the Medical College of Wisconsin that he completed an elective in palliative care.

“I fell immediately in love with it the first day,” he said. “This was a field devoted to working with things you can’t change and dealing with a lack of control, what it’s like to live with these diagnoses. This was a place where I could dig into my experience and share that with patients and families. This was a place where my life story had something to offer.”

Creating a New Form of Palliative Care

Miller went on to complete a fellowship at Harvard Medical School in hospice and palliative medicine. He became a palliative care physician at UCSF Health in San Francisco, and later directed the Zen Hospice Project, a nonprofit dedicated to teaching mindfulness-based caregiving for professionals, family members, and caregivers.

Gayle Kojimoto, a program manager who worked with Miller at UCSF’s outpatient palliative care clinic for cancer patients, said Miller was a favorite among patients because of his authenticity and his ability to make them feel understood.

“Patients love him because he is 100% present with them,” said Kojimoto. “They feel like he can understand their suffering better than other docs. He’s open to hearing about their suffering, when others may not be, and he doesn’t judge them. Many patients have said that seeing him is better than seeing a therapist.”

BJ Miller sits on a gurney at Northwestern hospital on his way

to a skin graft about 2 years after the accident.

In 2020, Miller co-founded Mettle Health, a first-of-its-kind company that aims to reframe the way people think about their well-being as it relates to chronic and serious illness. Mettle Health’s care team provides consultations on a range of topics, including practical, emotional, and existential issues. No physician referrals are needed.

When the pandemic started, Miller said he and his colleagues felt the moment was ripe for bringing palliative care online to increase access, while decreasing caregiver and clinician burnout.

“We set up Mettle Health as an online palliative care counseling and coaching business and we pulled it out of the healthcare system so that whether you’re a patient or a caregiver you don’t need to satisfy some insurance need to get this kind of care,” he said. “We also realized there are enough people writing prescriptions. The medical piece is relatively well tended to; it’s the psychosocial and spiritual issues, and the existential issues, that are so underdeveloped. We are a social service, not a medical service, and this allows us to complement existing structures of care rather than compete with them.”

Having Miller as a leader for Mettle Health is a huge driver for why people seek out the company, said Sonya Dolan, director of operations and co-founder of Mettle Health.

“His approach to working with patients, caregivers, and clinicians is something I think sets us apart and makes us special,” she said. “His way of thinking about serious illness and death and dying is incredibly unique and he has a way of talking about and humanizing something that’s scary for a lot of us.”

“Surprised by How Much I Can Still Do”

Since the accident, Miller has come a long way in navigating his physical limitations. In the early years, Miller said he was determined to do as many activities as he still could. He skied, biked, and pushed himself to stand for long periods on his prosthetic legs.

“For years, I would force myself to do these things just to prove I could, but not really enjoy them,” he said. “I’d get out on the dance floor or put myself out in vulnerable social situations where I might fall. It was kind of brutal and difficult. But at about year five or so, I became much more at ease with myself and more at peace with myself.”

Today, Miller’s prosthetics make nearly all ambulatory activities possible, but he concentrates on the activities that bring him joy.

“Probably the thing I can still do that surprises people most, including myself, is riding a motorcycle,” he said. “As for my upper body, I’m thoroughly used to living with only one hand and I continue to be surprised at how much I can still do. With enough time and experimentation, I can usually find a way to do what I need/want to do. It took me awhile to figure out how to clap! Now I just pound my chest for the same effect!”

Miller is an animal-lover and said his pets and nature are a large part of his self-care. His dog Maysie travels nearly everywhere with him and his cats, the Muffin Man and Darkness, enjoy making guest appearances on his Zoom calls. The physician frequently visits the desert in Southern Utah and said he loves the arts, architecture, and design.

Dr BJ Miller waits before a recent speaking event with his dog, Maysie.

Miller’s advice for others who are disabled and want to go into medicine? Live out loud with your truths and be open about your disabilities. Too often, disabled individuals hide their disabilities, lie about them, or shield the world from their story, he said.

“These are rich, ripe experiences that are incredibly valuable to someone who wants to go out and be of service in the world,” he said. “We should be proud of our experiences as disabled people. The creativity we’ve had to exercise, the work-arounds we’ve had to employ, these should not be points of embarrassment, but points of pride. Anyone who wants to pursue clinical training of any kind should use these experiences explicitly. These are sources of strength, not something to be forgiven or tolerated or accommodated.”

The same goes for physicians who aren’t disabled but who have lived through hardship, pain, struggle, or adversity, he emphasized.

“Find a way to learn from them, find a way to own them,” he said. “Use them as a source of strength and the rest of the world will respond to you differently.”

Alicia Gallegos is a reporter for Medscape Business of Medicine based in the Midwest. She has previously written for the American Medical News, the ACP Internist, and the AAMC Reporter. Contact Alicia at [email protected] or via Twitter at @Legal_med

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article