It’s long after midnight when the bustling operating room suddenly falls quiet –- a moment of silence to honor the man lying on the table.

This is no ordinary surgery. Detrick Witherspoon died before ever being wheeled in, and now two wide-eyed medical students are about to get a hands-on introduction to organ donation.

They’re part of a novel program to encourage more Black and other minority doctors-to-be to get involved in the transplant field, increasing the trust of patients of color.

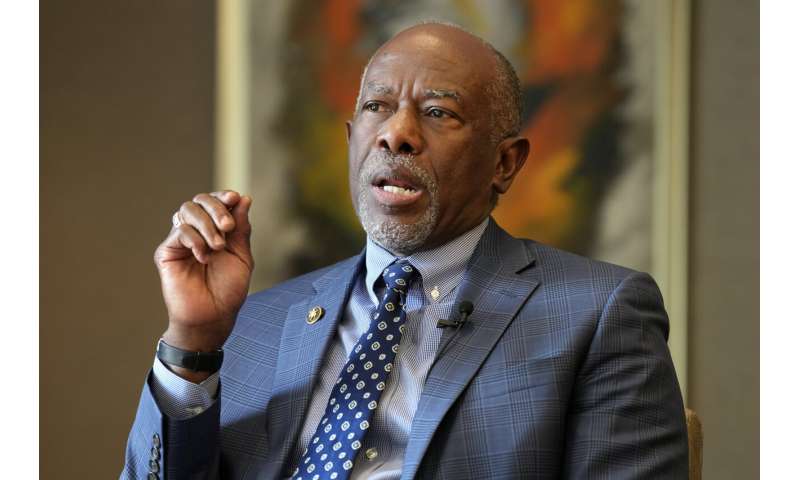

“There are very few transplant surgeons who look like me,” said Dr. James Hildreth, president of Meharry Medical College, which teamed with Tennessee Donor Services for the project—one of several by historically Black colleges and universities to tackle transplant inequity.

Fresh off their first year at Meharry, six students spent the summer shadowing the donor agency to learn the complex steps that make transplants possible: finding eligible donors, broaching donation with grieving families, recovering organs and matching them to recipients sometimes hundreds of miles away.

In the operating room, student Teresa Belledent worried she’d get emotional seeing a donor’s face –- especially this one, a Black father of six, just 44, who reminded her a bit of her own dad. Instead, calm descended as Dr. Marty Sellers, the organ agency’s surgeon, began retrieving the kidneys and liver while teaching Belledent and classmate Emmanuel Kotey.

“I’m able to feel sad and honor this person … and be able to focus on the act of helping other people,” said Belledent as the tired team began the two-hour drive back to Nashville from the Jackson, Tennessee, hospital.

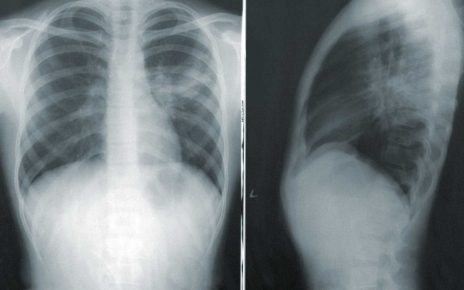

The night’s tougher lesson: Hours into the surgery the room falls quiet again. The donor had died of a brain hemorrhage but now Sellers has found undiagnosed cancer in his lungs. The kidneys and liver, already carefully placed on ice, can’t be used. Still, the corneas can be donated—and for the two students, the surgery offered a powerful teaching moment.

“I got to see so much and do so much—and trying is better than not,” Belledent said.

MISTRUST AND THE TRANSPLANT GAP

Despite record numbers of transplants in recent years, thousands die waiting because there aren’t enough donated organs—and some don’t get a fair chance. Black Americans are over three times more likely than white people to experience kidney failure. But they face delays in even being put on the transplant list and are far less likely than their white counterparts to get an organ from a living donor—the best kind.

Overall, Black patients make up 28% of the waiting list for all organs but account for just about 16% of deceased donors. Increasing donor diversity also helps improve the odds of finding a good match.

“How do we close that gap?” was the question Jill Grandas, Tennessee Donor Services’ executive director, took to Hildreth.

The Meharry students know mistrust of the medical system –- a legacy of abuses such as the infamous Tuskegee experiment that left Black men untreated for syphilis –- is a barrier both to organ donation and seeking care, such as transplants, that people may not be familiar with.

Austin Brown of Memphis said his grandfather “absolutely despised medicine,” and died of a heart attack after refusing an artery-clearing stent.

Belledent, of Miami, recalled her mother saying not to check the organ donor box when she got her driver’s license -– because of a widespread myth that doctors won’t work as hard to save the life of a registered donor.

“Now that I’ve seen the process, it’s crazy to even think about,” Belledent said. “In the ICU, no one’s looking through stuff and trying to find your license, look for the (organ donor) heart on there.”

Stacey Scotton of Cleveland, Tennessee, said a cook in Meharry’s cafeteria listed the reasons he’s heard “that it’s not a good idea to be an organ donor. And I’m able to now go in and comfort him and correct, you know, some of those disbeliefs.”

AWE IN THE OPERATING ROOM

Back at the Jackson, Tennessee, hospital, Kotey and Belledent are getting a very different anatomy lesson than medical students’ introductory lab with cadavers.

Machines keep oxygen and blood flowing to Witherspoon’s organs—and Kotey lets out a quiet “wow” upon touching a pulsating artery while assisting Sellers, the surgeon.

“It was the first time I’ve ever done anything like that. I didn’t want to mess up,” he said later.

Sellers gives precise instructions: Place your right hand here, pinch this spot, clamp that one. The students learn to trim fat from a kidney, stitch a biopsy wound and feel the lung nodule that proved cancerous –- opportunities they normally wouldn’t get until far later in training.

“I’m a firm believer that students can’t get really excited about something they’re not exposed to,” said Hildreth, who thinks early experiences like this could help diversify the transplant field.

Only 5.5% of transplant surgeons and less than 7% of kidney specialists are Black.

The Meharry students were stunned to learn how rare donation opportunities are. Only about 1% of deaths occur in a way that qualifies someone to even be considered, and hospitals must alert agencies like Grandas’ fast enough to evaluate candidates and approach families.

“It’s not like you go to the hospital, you die and you automatically become a donor. There’s a lot more moving parts,” said Sam Ademisoye of Lawrenceville, Georgia.

MATCHING ORGANS TO RECIPIENTS

In a Nashville ICU, Brown is learning bedside care for a deceased donor –- an 18-year-old motorcycle crash victim –- and how to match the organs on the national waiting list.

The heart is immediately claimed. But there’s a hitch with the lungs: Hospitals have said no for 16 patients, primarily because a week-old scan in the donor’s records suggested bruising.

Brown knows young donors’ organs usually are in high demand, and these lungs are working well.

“The denial, that blows my mind,” he said, helping nurses take the risky step of moving the body for another CT scan to prove the lungs really are fine.

The gamble pays off and the next transplant center in line grabs them.

The many steps to successful donation “are like gears in a machine and the entire machine breaks down if one gear fails. That’s my biggest takeaway,” said student Mikhail Thanawalla of Scottsbluff, Nebraska.

WHAT MAKES THE DIFFERENCE FOR FAMILIES

What the students may remember most were grieving families who shared their donation experience.

Daphne Myers, struggling with her son’s death at 26, initially was ready to refuse.

“I remember my reaction: I don’t want to talk about that,” Myers said. “I wasn’t educated on it. My generation wasn’t raised to be organ donors.”

But the donor representative didn’t make that request, instead asking Myers all about her son—how Haston Stafford Myers Jr. always helped others and loved to sing. Only then did Myers learn her son was a registered organ donor and realized she supported his choice.

“She was caring,” Myers recalled. “That changed my opinion, changed my mind. … The impact you guys can have on families, the caring that comes along with doing your job, it makes all the difference.”

-

Meharry Medical College students Emmanuel Kotey, center, and Teresa Belledent, right, observe an organ recovery surgery June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. Kotey thinks he’ll become a general practitioner and pledges his patients “young to old, will know about organ donation.” Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Meharry Medical College student Emmanuel Kotey watches as Dr. Marty Sellers, right, removes the liver and kidneys from an organ donor June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. Sellers gives precise instructions: place your right hand here, pinch this spot, clamp that one. The students learn to trim fat from a kidney, help with a biopsy and stitch the wound, and feel the lung nodule that proved cancerous –- opportunities they normally wouldn’t get until far later in training. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

An organ recovery team works to remove the liver and kidneys from a donor June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. Only about 1% of deaths occur in a way that qualifies someone to even be considered for donations, and hospitals must alert agencies fast enough to evaluate candidates and approach families. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Dr. Marty Sellers hands the liver of an organ donor to LPN scrub nurse Ashton Conrad, left, on June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. Cancer was later found in the donor’s lungs so the liver couldn’t be used for transplant. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Deana Clapper, associate executive director of Tennessee Donor Services, left, photographs a liver after it was removed from an organ donor on June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. The photograph and other information is sent on to the transplant team of the waiting organ recipient. Cancer was later found in the donor’s lungs so the liver couldn’t be used. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

A liver is prepared for transport after it has been removed from an organ donor June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. Cancer was later found in the donor’s lungs so the liver couldn’t be used for transplant. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Dr. Marty Sellers, left, and Meharry Medical College students Emmanuel Kotey, second from right, and Teresa Belledent, right, examine a kidney after it was removed from an organ donor on June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. Cancer was later found in the donor’s lungs so the kidney couldn’t be used for transplant. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

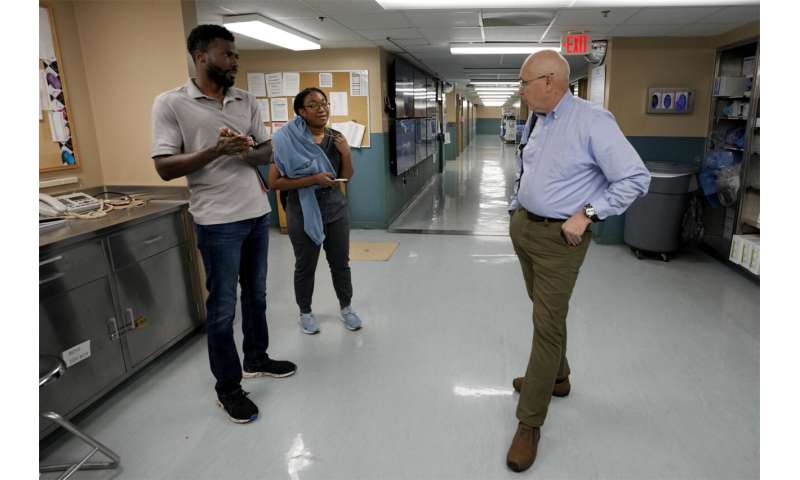

Dr. Marty Sellers, right, talks with Meharry Medical College students Emmanuel Kotey, left, and Teresa Belledent, center, after an organ procurement surgery June 15, 2023, in Jackson, Tenn. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Dr. James Hildreth, president and CEO of Meharry Medical College, speaks during an interview June 15, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn. “I’m a firm believer that students can’t get really excited about something they’re not exposed to,” said Hildreth, who thinks early experiences like this could help diversify the transplant field. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Meharry Medical College students Samuel Ademisoye, left, and Austin Brown, center, take part in a discussion with Michael Clay, Director of Family Services, right, at the Tennessee Donor Services headquarters June 16, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn. Brown of Memphis says his grandfather “absolutely despised medicine," and died of a heart attack after refusing an artery-clearing stent. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Tennessee Donor Services Executive Director Jill Grandas works in her office June 15, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn. Overall, Black patients make up 28% of the waiting list for all organs but account for just about 16% of deceased donors. Increasing donor diversity also helps improve the odds of finding a good match. “How do we close that gap?” was the question Jill Grandas, Tennessee Donor Services’ executive director, took to Dr. James Hildreth, president of Meharry Medical College. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Meharry Medical College student Mikhail Thanawalla, right, watches and listens as Sonya Smith, a referral screening specialist, takes a call at the Tennessee Donor Services headquarters June 15, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn. The many steps to successful donation “are like gears in a machine and the entire machine breaks down if one gear fails. That’s my biggest takeaway,” says Thanawalla of Scottsbluff, Neb. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Meharry Medical College student Mikhail Thanawalla talks with Daphne Myers, right, after Myers spoke with a group of Meharry students June 17, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn., about the decision of her late son to be an organ donor before his death at age 26. A donor representative asked Myers all about her son — how Haston Stafford Myers Jr. always helped others and loved to sing. Only then did Myers learn her son was a registered organ donor and realized she supported his choice. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

-

Daphne Myers, right, and her daughter, Latrice Gardner, hold a picture of Myers’ son and Gardner’s brother, Haston Myers Jr., on June 17, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn. Earlier, the two talked to a group of Meharry Medical College students about Haston Myers’ decision to be an organ donor before his death at age 26. A donor representative asked Myers all about her son — how Haston Stafford Myers Jr. always helped others and loved to sing. Only then did Myers learn her son was a registered organ donor and realized she supported his choice. Credit: AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

It’s far too soon to know if the program pointed students to new career paths. But next year, Grandas plans to also invite students from a historically Black nursing school.

Kotey thinks he’ll become a general practitioner and pledges his patients “young to old, will know about organ donation.”

Belledent, though, has long wanted to become a surgeon. She spent her childhood in Haiti and recalls family friends with kidney disease and no access to transplants. Specializing in transplant surgery “is definitely on the list because I like the idea of being able to give someone a second chance.”

© 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

Source: Read Full Article