Mount Sinai researchers have discovered a previously unknown mechanism in which not-yet-malignant cells from early breast cancer tumors travel to other organs and, eventually, “turn on” and become metastatic breast cancer.

The researchers, who reported in Cancer Research in April, also showed the ability of the transcription factor NR2F1, a protein that controls a gene’s outward expression, to block the pre-malignant cells from ever disseminating, which could be a crucial diagnostic tool to predict relapse.

“The current challenge for the management of treatment of early-stage breast cancer patients (for instance, patients who have non-invasive lesions such as ductal carcinoma in situ), is that even though local invasive recurrences are reduced after surgery or surgery with radiation, the risk of dying from breast cancer remains the same,” said the study’s lead author Maria Soledad Sosa, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Pharmacological Sciences, and Oncological Sciences, at The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai. “This suggests that before detection and removal of the invasive tumor mass, some pre-malignant cells disseminated and lodged at other sites, waiting for later reactivation. The identification of an ‘early dissemination signature’ in the breast tissue that could identify patients at risk of developing later relapses, who are therefore candidates for systemic therapy, is crucial to reduce mortality in these patients.”

A small but significant percentage of women with early-stage breast cancer never progress into an invasive breast tumor, which is the expected course of metastatic breast cancer. Instead, they die after their pre-malignant lesion reoccurs only in other organs, essentially becoming an unexpected, silent killer. Until this study, the mechanism by which pre-malignant cancer cells acquire mobile and invasive features that allow dissemination and colonization in other organs was not clearly understood.

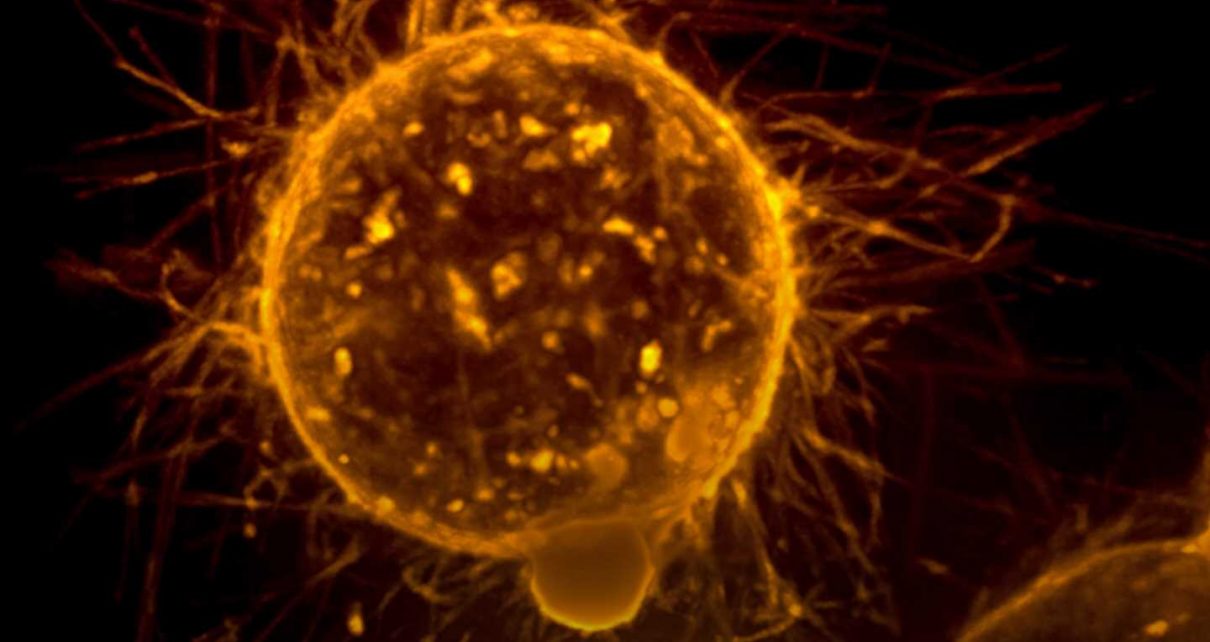

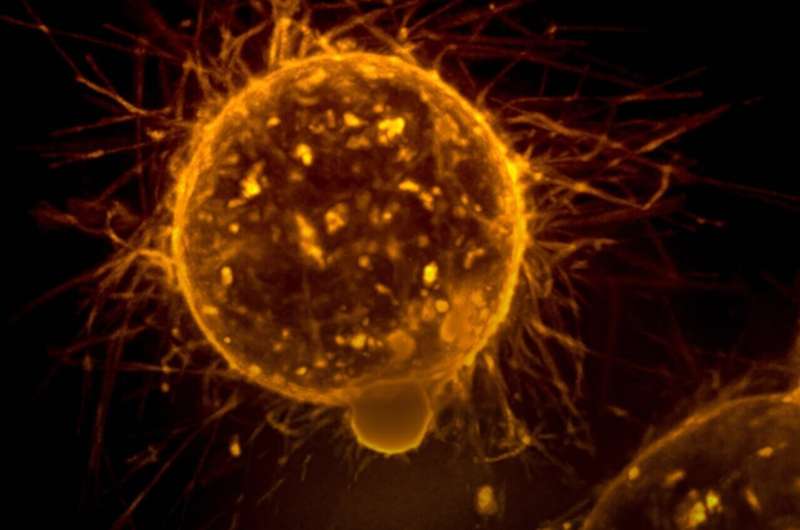

Researchers used animal models and pre-malignant breast cancer cells from patients, 3D cultures, and high-resolution microscopy to investigate how these pre-malignant cells disseminate. The authors found that the pre-malignant cells downregulated the levels of NR2F1, which helped prompt dissemination along with the upregulation of PRRX1, a master regulator of invasive phenotype.

Source: Read Full Article