Differences in biological sex can dictate lifelong disease patterns, says a new study by Michigan State University researchers that links connections between specific hormones present before and after birth with immune response and lifelong immunological disease development.

Published in the most recent edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study answers questions about why females are at increased risk for common diseases that involve or target the immune system like asthma, allergies, migraines and irritable bowel syndrome. The findings by Adam Moeser, Emily Mackey and Cynthia Jordan also open the door for new therapies and preventatives

“This research shows that it’s our perinatal hormones, not our adult sex hormones, that have a greater influence on our risk of developing mast cell-associated disorders throughout the lifespan,” says Moeser, Matilda R. Wilson Endowed Chair, professor in the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences and the study’s principle investigator. “A better understanding of how perinatal sex hormones shape lifelong mast cell activity could lead to sex-specific preventatives and therapies for mast cell-associated diseases.”

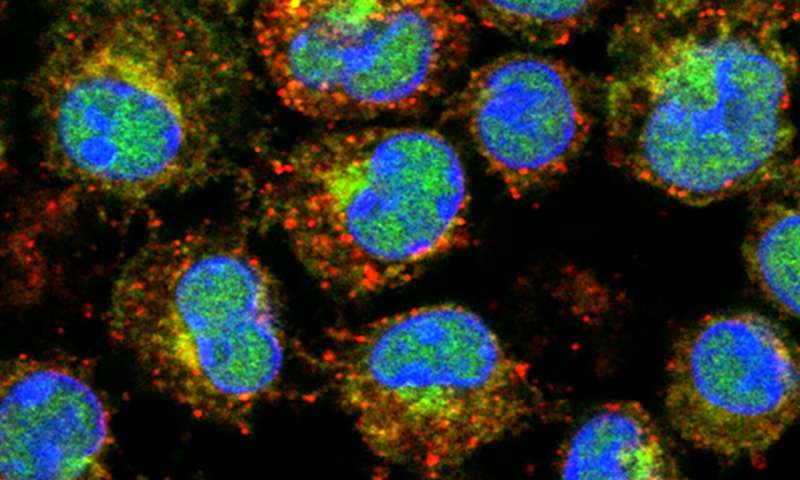

Mast cells are white blood cells that play beneficial roles in the body. They orchestrate the first line of defense against infections and toxin exposure and play an important role in wound healing, according to the study, “Perinatal Androgens Organize Sex Differences in Mast Cells and Attenuate Anaphylaxis Severity into Adulthood.”

However, when mast cells become overreactive, they can initiate chronic inflammatory diseases and, in certain cases, death. Moeser’s prior research linked psychological stress to a specific mast cell receptor and overreactive immune responses.

Moeser also previously discovered sex differences in mast cells. Female mast cells store and release more inflammatory substances like proteases, histamine and serotonin, compared with males. Thus, female mast cells are more likely than male mast cells to kick-start aggressive immune responses. While this may offer females the upper hand in surviving infections, it also can put females at higher risk for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

“IBS is an example of this,” says Mackey, whose doctoral research is part of this new publication.

“While approximately 25% of the U.S. population is affected by IBS, women are up to four times more likely to develop this disease than men.”

Moeser, Mackey and Jordan’s latest research explains why these sex-biased disease patterns are observed in both adults and prepubertal children. They found that lower levels of serum histamine and less-severe anaphylactic responses occur in males because of their naturally higher levels of perinatal androgens, which are specific sex hormones present shortly before and after birth.

“Mast cells are created from stem cells in our bone marrow,” Moeser said. “High levels of perinatal androgens program the mast cell stem cells to house and release lower levels of inflammatory substances, resulting in a significantly reduced severity of anaphylactic responses in male newborns and adults.”

“We then confirmed that the androgens played a role by studying males who lack functional androgen receptors,” says Jordan, professor of Neuroscience and an expert in the biology of sex differences.

While high perinatal androgen levels are specific to males, the researchers found that while in utero, females exposed to male levels of perinatal androgens develop mast cells that behave more like those of males.

“For these females, exposure to the perinatal androgens reduced their histamine levels and they also exhibited less-severe anaphylactic responses as adults,” says Mackey, who is currently a veterinary medical student at North Carolina State University.

In addition to paving the way for improved and potentially novel therapies for sex-biased immunological and other diseases, future research based will help researchers understand how physiological and environmental factors that occur early in life can shape lifetime disease risk, particularly mast cell-mediated disease patterns.

Source: Read Full Article